“ Later, they made him out a prairie Christ

To sate the need coarse in the national heart— “

Lincoln

—Delmore Schwartz

Linx: An intimate portrait of the man, his times, myth, and folklore.

Stagecraft (1998)

The first of the Linx series examines how Grant’s alcoholism arguably affected the way he waged war and how two very different histories (English—two Queen Marys and American—First Lady Mary Todd) can easily be conflated and confused by time, memory, loss, and the trauma of war. Finally, it depicts how the power of specific images and words remain and resonate in our consciousness. The Mathew Brady studio’s practice of posing and staging the battlefield dead for more dramatic effect, together with the histrionic descriptive prose of Civil War writing (both of the era and contemporary times) have forever changed the American public’s perceptions of war, valor, and sacrifice

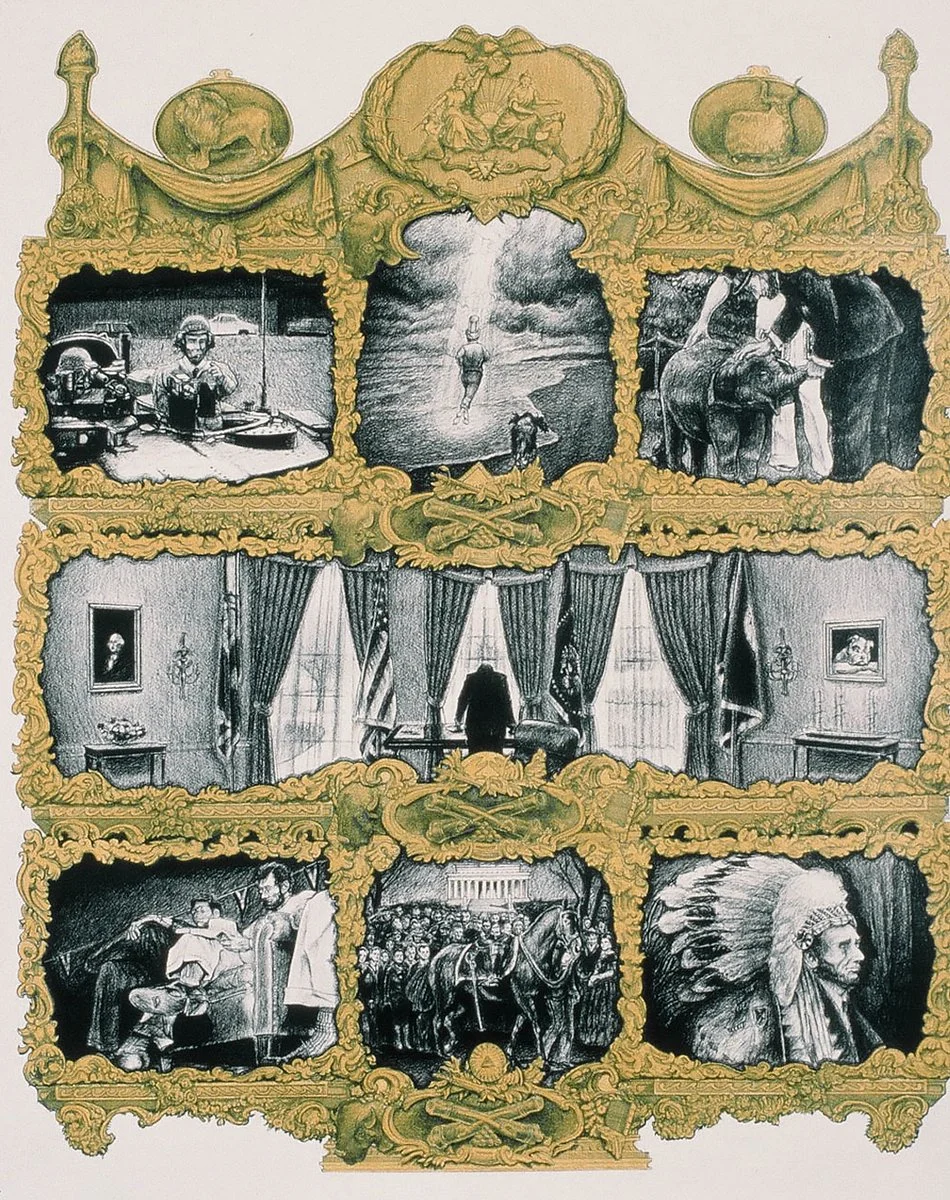

The Liturgy—a Rubric Presidential (1998)

This work poses several questions. If Lincoln is our greatest president, what makes a great president and a great leader? What attributes do we expect and what measures do we use to determine greatness? Is Abraham Lincoln the best measure of success? Here are six panels and several attributes required for greatness. All these drawings are based on famous photographs of former presidents or presidential wannabes, each with Lincoln’s head transposing theirs, each functioning as a box to be checked asserting the following presidential character traits:

Upper left, (Commander) Michael Dukakis: lower right, (Chief) Calvin Coolidge. Upper right, (Benevolent) Ronald Reagan petting an elephant; lower left, (Hard working) Adlai Stevenson with a hole in the sole of his shoe.

In the central panel is (Culpable and Enduring) John F. Kennedy shouldering the burden of being the leader of a superpower, in October of 1962, in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The bottom center; is (self-sacrifice) Kennedy’s funeral procession led by the riderless horse, a tribute to the fallen leader and symbol of the ultimate price of power.

The top center shows Robert F. Kennedy as depicted on the cover of “Life Magazine” the week of his death. Bobby, the inheritor of the Kennedy Camelot legacy, the one remaining hope at the end of the civil rights era, wearing Lincoln’s hat, perhaps the crown (?) at the moment of apotheosis.

1862 (1999)

1862 Portrays a privately tormented Lincoln. In February of 1862 first lady, Mary Todd and President Lincoln lost their youngest son, Willie. Just twelve, he was, by all reports, the couple's favorite of their three sons. So despondent was Lincoln that there was no official White House correspondence for days afterward, and Mary’s sorrow was so wretched that Lincoln worried for her sanity. Console her though he tried, he could barely contain his own grief.

In 1862, despite Grant's victories at Ft. Donelson and Shiloh in the spring, the Union would be defeated a second time by Stonewall Jackson in August at the Second Battle of Bull Run. And in September, the ever-cautious George McClellan would allow Lee to retreat back into Virginia after the bloody Union victory at Antietam. The casualties for that one battle alone would total over 23,000. The deluge of death would continue for a full three years.

In recent years, much has been made of Lincoln’s supposed bouts of depression. In this work, I imagine the private Lincoln first wearing a barrel and suspenders, spinning about in it, then crawling through it

( some attempt to self-medicate?), and finally, clutching his knees in the fetal position as he bemoans the loss of his dearest Willie and the thousands of Civil War dead.

The Poet's Song (2000)

Pictured are poets Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman, two poets who waxed elegiacally about the rail-splitter.

Whitman had a connection with Lincoln. Though the poet and the President never met, the story goes Whitman would wave at Lincoln as he passed a certain street corner in Washington. Whitman would go on to write two eulogies to the assassinated President, his “fallen star!” The first, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” appeared in 1865 shortly after Lincoln's death and in 1867, “O Captain! My Captain!” was later added to Leaves of Grass.

It is Carl Sandburg, in his copious biography Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years, who wrote some of the most widely read and influential books about Lincoln. As one reads Sandburg’s Lincoln it becomes quite obvious that often he did not check his sources. In fact, it is best not to read Lincoln as factual text at all, but rather, as an epic romantic poem. About the Prairie Years Sandburg wrote, “It is a poem of America, the humble folk, and rough pioneers, of crude settlements . . . a poem of the human spirit, not of Lincoln’s spirit only.” Perhaps no other writer has added more to the barrel of folklore and myth about Lincoln—our “Prairie Christ”—than Carl Sandburg.